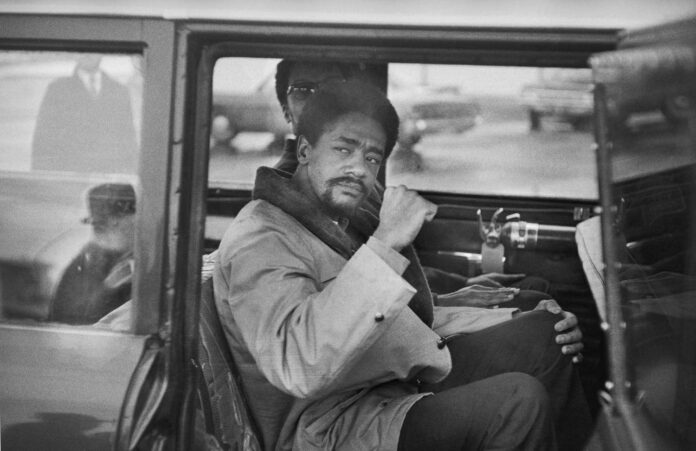

On October 22, 2025, Bobby Seale’s 89th birthday, the City of Oakland renamed the intersection of 57th Street and Martin Luther King Jr. Way to Bobby Seale Way. It’s not just about honoring a legacy. It’s a formal recognition of Seale’s deep impact on the city and his role in helping to build one of the most community-driven movements in modern U.S. history.

Seale, who co-founded the Black Panther Party alongside Huey P. Newton in Oakland, helped develop the Party’s Ten-Point Program, a direct response to the conditions Black people faced in housing, education, employment, healthcare, and policing. But they didn’t stop at diagnosis, they created real-world responses.

While government officials debated how to address poverty, the Panthers got to work. They served thousands of children each week through their Free Breakfast for Children Program, which eventually influenced national school nutrition policies. They opened People’s Free Medical Clinics, where people received healthcare and learned about diseases that disproportionately affected Black communities, like sickle cell anemia—a condition largely ignored by mainstream institutions at the time. They organized clothing drives, childcare, transportation for elders, and legal support. Together, these efforts formed a network of services they called “survival pending revolution.”

Bobby Seale made it clear: “Our job is to teach the people. Our job is to serve the people. We are the people’s revolution.”

That wasn’t just rhetoric. It was a framework—one that made care and political education central to liberation.

The Panthers have often been defined by their image: berets, leather jackets, and their right to self-defense. But what often gets overlooked is how organized, intentional, and service-focused they were. Their actions weren’t just reactive; they were proactive, often outpacing government programs in underserved communities.

They were also pioneers of what would later be called “copwatching,” monitoring police activity in Black neighborhoods and holding law enforcement accountable. Long before smartphones and livestreams, they showed up with law books, notepads, and a plan to protect. They didn’t come to escalate. They came to intervene when necessary and observe at all times.

Seale’s politics were never about division. They were rooted in coalition-building. Under his leadership, the Panthers worked alongside Latino, Asian American, Indigenous, and poor white communities. These partnerships laid the foundation for multiracial organizing efforts like the original Rainbow Coalition and sparked international solidarity. While critics often tried to frame him as anti-white, Seale clarified his values: “We don’t hate nobody because of their color. We hate oppression.”

Today, the Black Panther Party no longer operates as it did in the 1960s. Still, its core philosophy continues to shape community action. The legacy shows up in mentorship programs, mutual aid networks, food and health justice initiatives, and youth education projects.

You see this work carried on by groups like the Black Panther Party Alumni Legacy Network, which provides mentoring and education rooted in the Panthers’ original survival programs. The Huey P. Newton Foundation works to preserve and share the Party’s history in Oakland. The East Oakland Collective runs food and resource distribution programs grounded in self-determination and service. Phat Beets Produce pushes food justice through urban farming and community nutrition in areas once served by the Panthers. And the BPP Veterans Mutual Aid Fund supports former Panther members while demonstrating that community care doesn’t end with the headlines; it is ongoing work.

When you see youth in Oakland learning their history and leading food drives, when you see community-run clinics offering care without insurance, when you hear Hip Hop artists reclaiming voice and space, that is Bobby Seale’s legacy—alive and active.

This is why Hip Hop has always resonated with the Panthers’ energy. Not just in aesthetics, but in function. Artists like Public Enemy, Dead Prez, Kendrick Lamar, and Talib Kweli, along with organizations like Hip Hop For Change (Oakland and San Francisco), have taken up the same call: educate, empower, organize, and build.

Few captured that connection more clearly than KRS-One, who in 1995 delivered this line in Ahh Yeah:

“The Black Panther is the Black answer for real / In my spiritual form, I turn into Bobby Seale.”

If the intersection of 57th Street and Martin Luther King Jr. Way had the mic, this would be the lyric describing its own transformation—a line that embraces revolutionary Black history and identity. Bobby Seale Way is more than a marker of geography. It holds memory, movement, and meaning.

Happy Birthday, Bobby Seale. You aren’t just a historical figure; you’re an integral part of the cultural framework that continues to inspire.

All Power to the People.

Sources

- KRS-One, Ahh Yeah (1995). Lyrics via Genius: https://genius.com/Krs-one-ah-yeah-lyrics

- KQED: “Oakland Honors Black Panther Bobby Seale With Street Renaming”

https://www.kqed.org/arts/13982568/bobby-seale-way-street-renaming-black-panthers-oakland - Oakland North: “Oakland Honors Black Panther Co-Founder Bobby Seale With a Day and a Street”

https://oaklandnorth.net/2025/10/28/oakland-honors-black-panther-co-founder-bobby-seale-with-a-day-and-a-street/ - Stanford University: “The Black Panther Party and Health Care”

https://web.stanford.edu/class/e297c/poverty_prejudice/medicaid/blackpanther.htm - Washington Post Magazine: Interview with Bobby Seale

https://www.washingtonpost.com/lifestyle/magazine/bobby-seale-of-the-black-panthers-you-cannot-fight-racism-with-racism-you-have-to-fight-it-with-solidarity/2020/07/27/c4042aec-bfa6-11ea-9fdd-b7ac6b051dc8_story.html - BlackPast.org: “The Black Panther Party (1966–1982)”

https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/black-panther-party/ - AZQuotes: Bobby Seale Quotations

https://www.azquotes.com/author/13247-Bobby_Seale - Black Panther Party Alumni Legacy Network: https://bppaln.org

- Huey P. Newton Foundation: https://hueypnewtonfoundation.org

- East Oakland Collective: https://eastoaklandcollective.com

- Phat Beets Produce: https://www.instagram.com/phatbeetsoakland/

- BPP Veterans Mutual Aid Fund via Community Movement Builders:

https://www.communitymovementbuilders.org/national-projects/bpp-veterans