“On June 14, 2022, The Honorable Dupré L. Kelly became the first platinum-selling Hip Hop artist in the United States of America to win elected office. As West Ward Councilman, he is governing where he grew.”

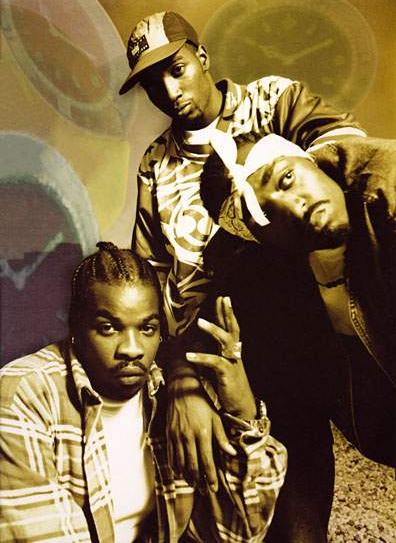

Those lines are from the personal website of Dupré Kelly. Hip Hop heads and music fans will better know Dupré Kelly as Doitall, the emcee who along with DJ Lord Jazz and Mr. Funke, made up the rap group Lords of the Underground. In 1993, Lords of the Underground released Here Come the Lords, featuring beats from legendary producer Marley Marl and K-Def, a record generally regarded as a golden era Hip Hop classic. The lead single from that album, Chief Rocka, still gets steady play on air and in clubs today. The Lords would make a mark on Hip Hop history representing their era and even more so representing their city. That city is Newark, New Jersey, which is also where Dupré Doitall Kelly was recently elected a Councilman in the city government.

Newark, is a place that has been through many changes in its time as New Jersey’s largest city. Its story includes so many fibers in the fabric of the history of music, film, social movements, and more recently Hip Hop. The current mayor of Newark at the time of this writing is Ras Baraka, son of the revolutionary poet and playwright Amiri Baraka. Ras Baraka, a poet himself, also appeared on the Fugees’ multi-platinum album, The Score as a character in the skits running between songs. The dialogue of his contributions on the album represented an everyday Newark resident, someone with the grit of growing up in a city that Time Magazine ranked as the most dangerous city in America in the year that The Score was released. But the character wasn’t just gritty, he was also politically aware and self-reflective. His dialogue drew out a complexity that personifies a uniquely changing environment of shifting sand that would ironically earn the nickname of Brick City. The Bricks is a place where change and action very much mirror many of the pathways Hip Hop has carved into the psyche of the nation in which it was born. Ras Baraka finishes his opening monologue after an introduction from DJ Red Alert on the the intro track of The Score with a line that echoes throughout the rest of the album:

“And we gon’ make what we believe manifest… ’cause if you ain’t ready now, you ain’t never gon’ be ready!”

The recent election of Dupré Kelly to city council is evidence of the ways that Hip Hop plays a part in shaping Newark’s history but that reality is also underscored by the role Newark has played in shaping Hip Hop. To understand that relationship, it’s useful to look back on a few of the events that formed the course of the winding history of Brick City.

Before Lords of the Underground, Queen Latifah, The Outsidaz, and of course Redman, the superstar emcee that made Da Bricks a household name, there were other lists of names of stars born in Newark. Closer to the era that Amiri Baraka and legendary jazz singer Sarah Vaughan were born in Newark, Jerry Lewis was also born there. Shortly later would come names like Joe Pesci and Ray Liotta. Newark, which in 1966 would take place alongside Washington DC as some of the first large cities in the United States with an African American majority, went through a tenuous shift to arrive at that point.

The years between 1940-1970 are often referred to as the Second Great Migration of African American families out of the south and into other urban areas of the country. During that time period, Newark experienced the most dramatic racial population shift of any major city, with the African American population growing from 10.6% to 54.2%. The northern cities represented a greater safety from the violent racism of the Jim Crow southern states but still existed in a nation grappling deeply with structural racism and its effects. Migrants from the south followed opportunity while fleeing the violence, segregation, and repression of their hometowns but found new problems in integrating into white dominant environments like Newark at the time.

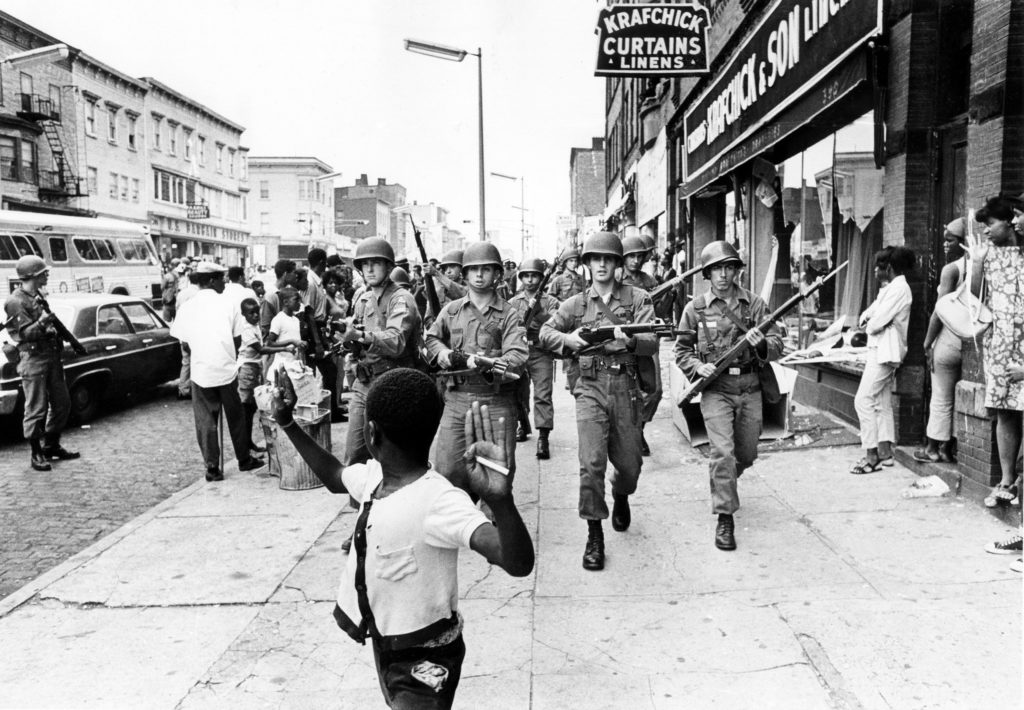

Before the city’s major population shift and the rise of the brick tenement buildings that gave Newark its nickname, hostility manifested into violent outbursts such as a dispute in 1917 reportedly arising from a dice game involving black and white youths that turned into hours of clashing mobs armed with guns, knives, clubs, and bricks. Many residents were injured and fifteen black youths were arrested. Racial tension and institutional inequality continued to bubble, later spilling over into the contentious events that history would record as the 1967 Newark Riots. In July of that year, the aftermath of the arrest and police beating of a black taxi driver was five days of violence that left 26 dead and over 200 people seriously injured. Blocks of the city were razed by fire and looting, leaving a monetary toll of the damage at an estimated $10 million.

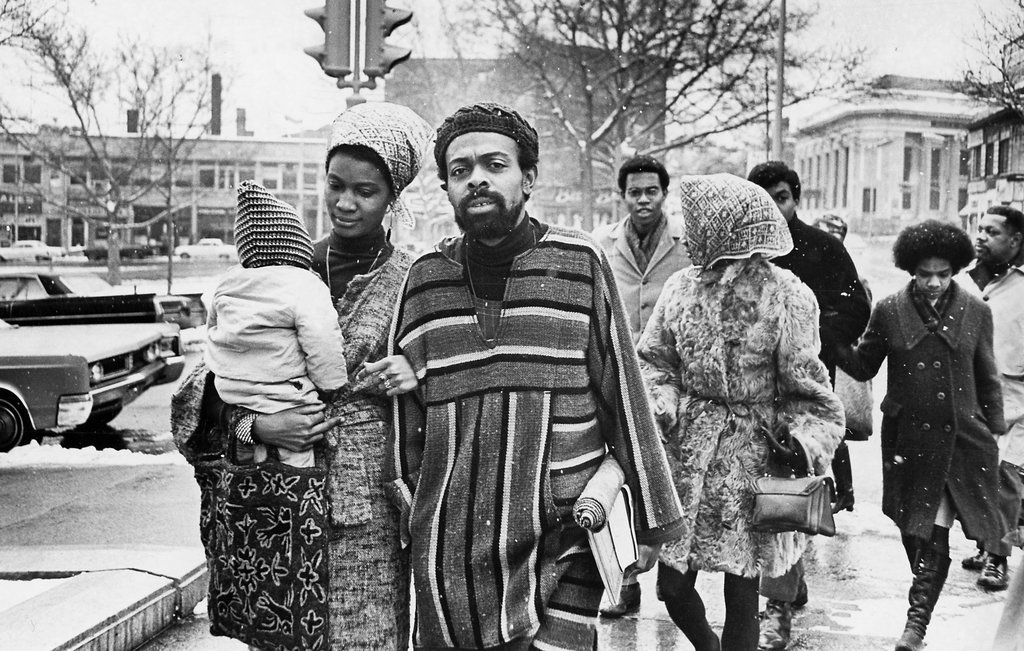

The events in Newark in 1967 were predicated by recent upheavals in nearby Jersey City and Harlem and also across the country in the Watts neighborhood of Los Angeles. While the media deemed these events as riots, many of the people involved had a different perspective. Amiri Baraka, already an active artist and community organizer at the time, reframed the concept of a race riot.

“Rebellion, I call it.” Baraka told the New Times in a 2012 article reflecting on the deadly summer of ‘67. “The idea that the city would blow up was obvious.” He was arrested for his part in the protests and taken to Dominick Spina, the police director at the time’s office. “I fell on the floor. Spina says, ‘We got you,’ like some grade-B movie. I say, ‘Yes, but I’m not dead yet.’ That’s the level things were at.”

35 years after the summer of ‘67, Amiri Baraka was awarded the title of Poet Laureate of New Jersey by Governor Jim McGreevey in August of 2002. He was forced to relinquish the title after reading his controversial poem “Someone Blew Up America” a month later at the Geraldine R. Dodge Poetry Festival. The following year, the New Jersey State Legislature abolished the position. In the same New York Times interview cited above, Baraka reflected on the power of words and art and their unique role as bedfellows to social change.

“Poetry is underrated,” he said to the reporter. “So when they got rid of the poet laureate thing, I wrote a letter saying, ‘This is progress. In the old days, they could lock me up. Now they just take away my title.’ ”

This complex interaction between artists and the oppressive conditions stemming from the social ills of their environment is fluid and messy but creates a lens to better understand the world that Hip Hop was born within. The course of a culture that rose from the ashes of burning buildings, such as the ones in the Bronx that some of Hip Hop’s earliest DJs walked out of with new turntables during the New York City Blackout of 1977, is intrinsically linked to Newark and other cities like it resisting injustice with bricks, poems, and breakbeats.

The link between rebellion, politics, and Hip Hop is carried from the very roots of its art form. As the early founders of the form pass away to become names in history, the following generation continues to take the story in new directions. The original members of the outspoken activist poetry group The Last Poets, who Amiri Baraka termed as “the prototype rappers” have all passed away, except for one surviving member. Amiri Baraka passed away himself in Newark Beth Israel Medical Center in 2014. The spirit of his work lives on in the city where he and his wife Amina Baraka respectively founded schools and women’s conferences, wrote, spoke, lived, and raised their children.

Ras Baraka ran for mayor and lost several times before he was elected and re-elected for his third term in 2022, this time with more than 80% of the popular vote in his favor. Before that, he was councilman in the South Ward. One of his brothers was his chief of staff and another was his chief of security. Dupré Doitall Kelly ran and lost and tried again before being elected as the West Ward Councilman. Before that he was in the streets doing things that many people active in the Hip Hop community would be familiar with from providing free haircuts to youth, to organizing food and water donations to those brick project buildings, and on to creating 211 Community Impact, a community educational program designed to foster interest in civic activity in local youth.

Politics notwithstanding, the election of a member of Lords of the Underground into public office is a big moment in the history of Hip Hop. It’s not that Doitall is the first rapper to mix rebellious art with establishment politics. Geto Boys frontman Scarface ran for Houston City Council in 2019, narrowly losing the seat to a local educator, Carolyn Evans-Shabazz in a run-off. The Grammy-winning rapper and ghost-writer, Rhymefest lost a bid for alderman of the 20th Ward in his hometown of Chicago by less than 400 votes and used the platform to set up a meeting with then-British Prime Minister David Cameron to discuss the nature of Hip Hop and its impact on society. Anotnio Delgado, the Lieutenant Governor of New York state at the time of this writing, as well as Harvard Law graduate and Rhodes Scholar, was attacked by his political opponents for lyrics on a rap album he released in his younger days under the name AD the Voice.

The reason why Dupré Doitall Kelly representing the city he is from in political office is so important is because it reminds us that there are many ways to approach social growth and Hip Hop is complex enough to not be bound by any of them. His election is further proof that despite tremendous hurdles that may exist, walls can be broken. The story of his campaign draws out the story of Newark and places those details within the story of Hip Hop, and vice versa. It reminds us where we were, where we are, things that have persisted or changed, and those reflections speak of the open ended possibilities of where we might go.

Dupré went on record to say that a conversation with Tupac Shakur inspired what would become his political career. Speaking just after his election, he told the story of him and Tupac in a hotel room on tour when Tupac told him, “We have to deal with legislation. If we don’t do that, those laws will never be made for us.” When Doitall replied that they were rappers and rappers aren’t politicians, Tupac said, “That’s our problem. We have to get to the table and be included in the conversation.” Regardless of the many feelings people may have of any political candidate or the general nature of electoral politics in social change, Hip Hop just earned a new seat at a table. The story of any living and breathing culture is about change. Hip Hop and the world around it continue to change. As the community that makes up the culture keep their eyes on where it may be headed, they prepare for what’s next because like Ras Baraka said on The Score, “if you ain’t ready now, you ain’t never gon’ be ready!”